Photo by Michal Franczak

“Your future is someone else’s past.”

These were the first words shared by Pieter van Glind before he brought us along for a journey to different destinations through HUB-IN’s Atlas to discover three interesting cases of urban regeneration in old abandoned buildings in European cities. He started in Bratislava, Slovakia, at a market hall, stopping by a Slovakian tabaco factory in Košice, and then made his way up to Tallinn, Estonia to an industrial complex. On this journey, we saw how these once obsolete and neglected industrial and traditional sites had been transformed into thriving innovative, cultural, entrepreneurial and community hubs, filled with a myriad of people, activities and industries.

This was part of the webinar and side event of the first edition of the New European Bauhaus Festival, Business & Financing Models for Tomorrow’s Heritage, where HUB-IN joined forces with sister projects CENTRINNO and T-Factor to show audiences how to go transform abandoned historic urban spaces into sustainable, inclusive and beautiful spaces – aligning with the values of the New European Bauhaus.

Helping Jane save her city’s factory

Pieter’s goal with this virtual trip was not just for the fun of visiting cool sites throughout Europe, but was mainly to help Jane, a fictional character at the centre of our Webinar, in her mission to save her city’s abandoned factory. With a space full of potential, an enthusiastic community behind her, an interested group of creatives, and expressed interest from the municipality, Jane is ready to start, but does not know exactly which direction to take… By presenting examples of similar spaces that have been successfully brought back to life and highlighting the different business models behind them, Pieter was giving Jane insights to start her on the right path.

Besides Pieter van de Glind, we also heard from Francesco Cingolani and Alejandra Castro, who in the same spirit, gave examples of past experiences and concrete cases stemming from CENTRINNO and T-Factor networks, that could help Jane in her endeavour. Moderated by Brian Smith from Heritage Europe, we finished the hour-long discussion with concrete advice that Brian pulled from the three projects’ experiences for Jane to follow.

Although Jane is a fictional character, her story is very real. And the advice given to her as well.

What were the key lessons and advice from the cases presented? How did they respond to Jane’s main concerns?

The Key Ingredients to making a building come back to life

Jane’s first concern was to find the right recipe in order to make her efforts worthwhile. There are constant attempts to bring old buildings back to life, but not all are fruitful.

Why are some old buildings coming back to life while others are not? What really makes the difference?

Networks

Francesco Cingolani has an idea or two of what can make the difference, deriving from his experience and years of hard work bringing to fruition his own ambitious project. Seven years ago, he founded a creative and productive hub in the centre of Paris that he still runs today: Volumes. The story of Volumes is an inspiring case for Jane: an abandoned factory in the heart of Paris completely transformed into a flourishing, dynamic and innovative centre of “radical experimentation”. As we listened to Francesco recount his tale, images unfurled of a bustling and fabulous lab brimming with designers, creatives, chefs, food entrepreneurs, and community members.

A space of creation, experimentation, collaboration, that could be described as nothing less than “super cool”. Francesco agrees. Yes:

“Super cool… but…”

There is always a “but”. Francesco was not there to show us how amazing Volumes is and tell Jane she should do exactly as he did, he was there to show us the “buts” that Jane could learn from. He exposed the many challenges they faced over the years, and the lessons that they learned.

After five years of operation and non-stop activity, in 2019, Volumes sat down at a crucial point of their trajectory to reflect. Their business model was stable, but fragile; their community was vibrant, but excessively reliant on volunteers; the team was awesome, but overloaded and under too much pressure; the space was thriving, but filling up too fast and needed more room if it were to bring in new projects. Like any moment of crisis, this point of inflexion for Volumes presented them with the opportunity to innovate, change their model, and grow and scale their project as a result.

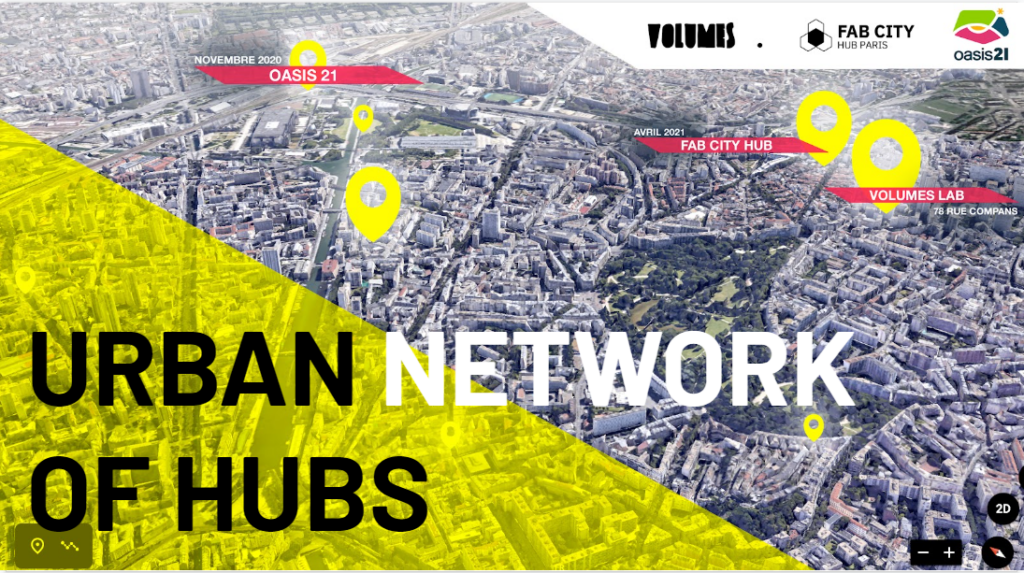

The new vision was to transform Volumes from a “hub” to an “ecosystem” – a network of connected hubs, each with its own identity and specificity, but that are able to work together, sharing resources and a business model, as a way of spreading the load between multiple centres. Volumes just had to poke its head out and look around them to find many more like-minded organizations and aspiring “hubs” that were grappling with the exact same challenges as they were. From some of these new connections, Volumes paired up with two other projects, Oasis21 and Fab City Grand Paris, co-founding a new company that would manage this network of hubs.

Community

One of the key lessons from this is that everything is easier when done in a group rather than on one’s own. This is why building community is an essential ingredient to bringing a space back to life. Your community today can become your team later on, which is a crucial foundation for any creative and collective hub.

This is one of the things that Volumes may have taken for granted and overlooked at the beginning: the importance of human resources. Today, human resources count for 15% of their operational costs, more than the project initially imagined. But these 15% are an essential pillar to the project’s success. Managing a series of hubs, even when it is easier because supported by stronger networks, needs a competent, motivated and well cared for team to carry it, especially in the early stages of the project.

Nurturing a community dedicated to the project goes beyond the team. Pieter van de Glind’s first stop in the HUB-IN Atlas at the old market hall in Bratislava, Stará tržnica, showed us how communities can drive urban regeneration processes. Although for years developers and investors attempted to (unsuccessfully) give a new life to this abandoned market hall, it was the joint effort of eleven citizens from different backgrounds taking on the management of the space that drove its successful regeneration. An important ingredient of their recipe: fostering a strong community at the core of the space’s existence.

They fostered this community mainly through social use of the space. Through mixed financing schemes, they were able to provide lower rent in order to lease to many community-oriented organisations. This is possible because the city, in exchange to renting the building to the Market Hall Alliance for a symbolic one euro per year for 15 years, has required that any revenue generated should be reinvested in the building’s renovation and maintenance. To involve the community in the process, the initiative regularly organized bazaar events where community members could donate materials and items that would go into the refurbishing of the space. They also created a community currency that could be used within the space. This community participation and ownership made them an essential part of the place’s fabric and essentially is what has kept it alive.

Temporary Activation

An important way to foster community around a space is to start involving them immediately in the regenerative process, to give them time to build and develop a connection to the space. However, this immediate integration could be at odds with the lengthy waiting periods of urban regeneration.

To tackle this paradox, Alejandra Castro, researcher from TU Dortmund University who works providing expertise to T-Factor on Transformation Labs, suggests an interesting solution: the temporary use of the space. This ingredient of “meanwhile spaces” is what T-Factor is betting on for successful urban regeneration, and is something Jane should think about too.

An effort to refurbish, revive and reinvent an abandoned space takes much time and effort, as Francesco’s experience clearly showed us. The long waiting time, inflexibility and rigidity of urban regeneration can at times harm the process and undermine its success. In the time a vision takes to be implemented and a building refurbished, if the community is not effectively engaged since the beginning, by the time the process is finished, the vision may have become obsolete.

T-Factor works to make these processes more agile and dynamic. Jane may feel intimidated by the amount of time and resources that must go into such a project, without knowing if the space will eventually activate. But, if she slowly starts bringing the space to life through temporary use, while she is still working on the refurbishment, she is not only already rallying community and activating the space, but also testing what the space can eventually become. Instead of having a fixed vision of what the end result will be, this leaves room for the vision to evolve, for new partnerships to arise, for the uses of the space to be reinvented, and for innovative governance models to be designed. It’s a perfect way to test ideas, while setting the field for new things to happen and for the vision to improve with the help of the community itself.

These small, temporary steps can reassure Jane and give her more confidence in the process – and essentially could make the difference between the space coming back to life or not.

Convincing key stakeholders

But even if you have the key ingredients to successfully bring this space to life, it is of little use if you do not have the key stakeholders – owners, municipalities and funders – on board to initiate the project, which is Jane’s second biggest concern.

How can we convince the owners of the building and the city that we can take the abandoned factory back to the days when it was a thriving community?

Communication

Before any of the other trials mentioned above, the first challenge Francesco faced when founding Volumes seven years ago was to convince the landlord and the banks that it was worth transforming this space into a creative hub. The notion of a “creative hub” was foreign to classic institutions such as banks: why would you have a model that relies on such wide-ranging professionals and fields, from architecture and design to food?

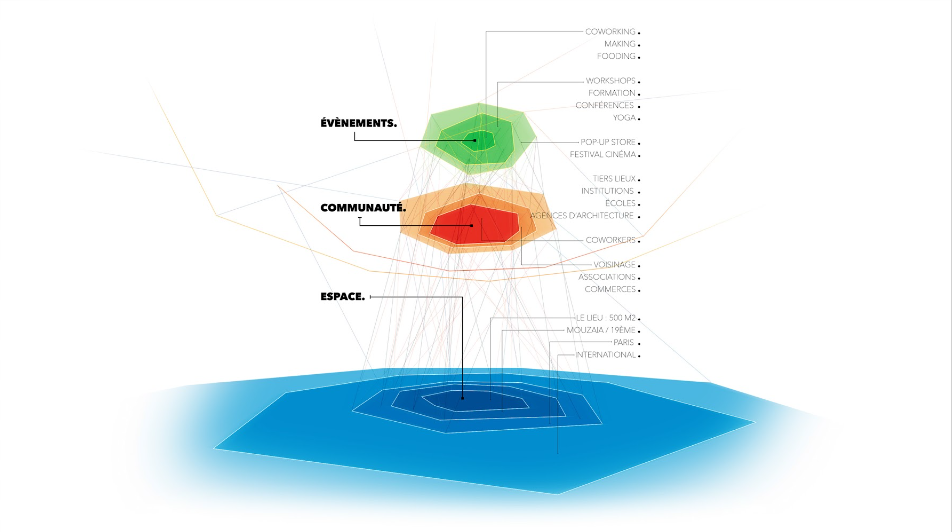

To tackle this challenge, Francesco insists on the importance of communications skills and using visual representations to explain your vision and model. For Volumes, they created a diagram explaining the concept of a creative hub, to illustrate its strength and solidity.

However, it is not only the content of what you present that matters, but also the context. In order to convince stakeholders that your project is worth supporting, you must have a good story to tell. And this story must be relevant to the stakeholders.

Pieter showed us a good example of this with his short stop at the old Tobacco Factory in Košice, Slovakia: Tabačka Kulturfabrik. A local civic association started organizing events in the old factory in 2009, ramping up the cultural activity in the area by bringing in more events, in addition to workspaces, community gardens, and a variety of creative businesses, including a printing studio and a recording studio. In parallel, the city of Košice was on a mission to become an artistic and cultural reference. Named cultural capital of Europe in 2013, it then developed a creative economy masterplan to become a Creative City by 2020. By favouring creative activities and events in their space and becoming a cultural and artistic hotspot in the city, the Tobacco Factory was thus able to ride the wave of energy, inserting itself in a favourable context, and as a result gaining public support and funds. This was an effective strategy, as the Tobacco Factory was able to rely mainly on public grants and funding from local and EU levels to refurbish the space and bring their project to fruition.

Pieter’s message: to tell a story that will speak to her stakeholders, Jane should look at what is relevant to them. What is her city’s priorities and what wave of energy could her project ride on?

Building Confidence

Telling a good story also means building confidence with your stakeholders. The Market Hall in Bratislava that Pieter brought us to earlier is a good example. After many failed attempts of bringing the space to life by multiple investors, the citizens that managed to do so were the ones who showed the municipality everything that is possible in the space by involving the community in diverse ways. Doing this directly feeds the storytelling as it is happening.

In the same way, creating “meanwhile spaces” allows to create trust within the community, showing the municipality and other stakeholders all the potential of the space. Hence, building confidence locally is key to convincing stakeholders that the regeneration project is worthwhile.

Making sustainable, inclusive, and beautiful spaces

Convincing the stakeholders and finding the ingredients to bring the space back to life are good first steps. But as Jane is a strong adherent to the New European Bauhaus values of beauty, inclusivity and sustainability, she also worries about another very important element once the project is off the ground:

How do we ensure that our regeneration efforts transform the abandoned factory into a sustainable, inclusive and beautiful space?

Governance

All three speakers echoed the same response: getting the governance right.

For Volumes, having an organic and collaborative approach is key to ensuring the inclusivity of these spaces. Instead of centralizing the management, they privileged a system where founding organisations govern in collaboration with user organisations, partners, nomad coworkers, founding members, team members and funder organisations. This lets users and clients also have their own input on how to manage the network.

Another important lesson Alejandra has for Jane from her experiences with T-Factor, is for her to get to know the regulatory wiggle room she will have in terms of action. This means understanding how the regulation can influence and allow for temporary use. Since a lot goes into activating a space, it is important to understand the starting level in terms of governance. Once you understand the bureaucratic and regulatory field and know your wiggle room, you can better identify the opportunities for temporary use.

Alejandra encourages Jane to find out if there is a temporary use agency in her city or an intermediary of sorts, such as a help desk that can liaise between the government, the owners and the users who want to engage with the site. These types of entities can be of great help to better understand the field and create flexible leasing contracts, subsidizations and use mechanics for vacant spaces.

For Pieter, good governance should be the right balance between stability and flexibility: maintaining openness and idealism in early stages, without compromising financial sustainability. Committing to reinvesting future profits the way the market hall in Bratislava is doing provides Jane with a good example. In this case, all progress being generated is invested back into the community.

In his last stop in HUB-IN Atlas, at an industrial complex in Tallinn, Telliskivi Loomelinnak, we have another example of how to establish a successful governance structure. Even though this project was originally privately funded, it is now a self-sustained community that runs as a community platform. When it was sold to a Swedish family group, it included a specific agreement that would protect the creative sector, giving way to a governance structure that would allow this creative area to emerge. The lesson here: in order to safeguard the beauty, sustainability and inclusivity of your space, it is important to set in stone anything you can at the start, setting the rules for the entity operating the building which can then be maintained in the future.

If you get the governance structure from the beginning, you can then build upon it and strengthen it with time.

Diversity

But Jane would then ask: what is the right structure of governance? If you follow closely the stories of Francesco, Alejandra and Pieter, you will notice that there is no one single solution, but always a mix of solutions.

This is the main lesson we can take from Pieter’s visit to three different sites of the HUB-IN Atlas. What they all have in common? They rely on a cocktail of approaches.

Diversity is necessary, not only in governance as Francesco pointed out with Volume’s collaborative governance structure, but also in the business model and the community itself. The old market hall in Bratislava, as well as the Tobacco factory in Košice and the industrial complex in Tallinn all house a wide range of activities, from private to public to non-profit. Bars, cafes, boutiques are side by side with co-working spaces, community gardens, markets, social associations, cultural workshops, event venues, public parklets… This not only creates a diversity in the backgrounds, expertise and points of views in the community that gathers and contributes to the space, but also in sources of income. Balancing stable and more volatile sources of income allows for the right equilibrium between stability and flexibility mentioned above.

In the case of the old market hall in Bratislava for example, the main source of income (60 to 70%) comes from the public-private events and workshops organized in the space. This is then complimented with a more stable income stream through rental to different types of entities, both commercial and social. As for the old Tobacco factory, the refurbishing of the building itself was in partially financed by the local government and in part supported by the local civic association who also invested in renovating and furnishing. The project came through with a patchwork of grants and funding from public institutions including the European Capital Grant Scheme as well as some national Slovakian programs.

The evolution of Volumes from Hub to Ecosystem also demonstrates how essential it is to have an open, diversity-oriented approach. Francesco encourages Jane to connect with what is around her and to go deeper and wider to seek out partners, similar initiatives, specialized skills, diversifying the project’s surrounding ecosystem. This allows to create strong alliances with a wide-range of expertise and methods, from which to build resilient and sustainable businesses.

Conclusion

All in all, what should Jane take away from (yet again) this patchwork of stories and cases?

After the three speakers had presented all their examples, Brian Smith drew all of these points together into three main lessons that could help Jane onto the right path. His advice:

1 – Even though there are many reasons that some buildings fail to be brought back to life – for Heritage buildings for instance this can be due to adaptability, lack of demand for desired uses, perceived extra cost – but most importantly it’s about leadership and resources. And this means resources not only in terms of finance, but also in terms of human resources. Focus on building a solid team and community, as Pieter and Francesco demonstrated with their examples.

2 – Whether you are trying to convince owners or municipalities, both want to be confident that you are capable of delivering a viable solution that has good community support. Here, a lot has to do with developing good communications skills and telling a compelling story. Alejandra contributes a different perspective by introducing the power of temporary use of spaces, which in itself can feed the storytelling that Pieter talks about, which helps build confidence. This helps build momentum step by step and create a buzz that turns potential investors’ heads.

3 – Turning the space into a beautiful, sustainable and inclusive space is a worthwhile mission that should be a constant throughout the process, especially considering it may be a long and winding road. Most importantly, you have to develop your solution tailor made to your place and community. This means you must have an open approach and connect to what is around you: go deeper and wider to seek out similar initiatives and the specialised skills that you need, to build your own local ecosystem that can help you maintain a sustainable business. Don’t wait too long to start activating the space, take advantage of the “meanwhile” – even if your first actions are temporary to start with, they will lead you to new possibilities and improve your vision.

Bringing us back to the context in which this whole discussion is taking place, Pieter points out:

“The New European Bauhaus Movement is not only a framework, but an attitude that can be powerful and help you change the world, there to show us that we can do things differently and there are ways to do so.”

So, what are you waiting for? If you have a project like Jane’s, you now know the basis on which to start building your idea. Follow the three main lines of advice that Francesco, Pieter, Alejandra and Brian drew out for us. And most importantly, don’t forget to have fun!

Resources

Re-watch the full Webinar.

For a general overview of different possible business and financing models, check out our report on the topic.

To find inspiration among more cases and examples with different models throughout Europe, check out the HUB-IN Atlas.

To delve into stories around creative hubs, check out Volumes.Media platforms. Listen to their podcast for inspiring interviews about local ecosystems for positive change.

Still not sure where to go from here? Looking for a network that can support you, give you inspiration and tools, and develop solutions alongside you? Then join the HUB-IN Alliance.